Common Ground News Service

16 December 2008

[Syndicated by the Middle East Times, Beirut’s Daily Star, Egypt’s Daily News and Al Arabiya]

[Read this column in Arabic, Urdu, French and Indonesian]

Negotiating with our adversaries is a tricky business, and with President-elect Barack Obama on the way in, most observers of US foreign policy are confident that negotiating is about to become the predominant foreign policy approach — for better or worse. They are mistaken, however, if they think this approach will be a drastic change.

In fact, in the last two years, though it is sometimes difficult to discern from White House press releases, President George W. Bush has actually been relying more and more on the very tactics that most observers have come to associate with Obama. In fact, in terms of broad foreign policy strategy, when it comes to opening the channels of negotiation and dialogue, four more years of Bush could have been alarmingly similar to those of Obama’s upcoming ones.

Consider, for instance, that after six years of refusing to negotiate with “rogue” governments or liberally labelled “terrorist groups”, the Bush administration has, since 2006, negotiated a long-lasting alliance with the Sunni insurgents in Iraq, many of whom are held responsible for killing thousands of American soldiers between the summer of 2003 and the fall of 2006. In addition, Washington led successful multilateral negotiations with North Korea to ensure a verifiable dismantling of Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons programme, which produced and successfully tested a nuclear device in 2006.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, the Bush administration has negotiated with Iran in order to reduce Tehran’s military and financial support of the Shi’a militias in central Iraq, and Washington has expressed increasing openness to negotiating with the non-Al Qaeda elements of the Taliban.

To claim, however, that Bush has been rectifying his disastrous policies is hardly absolution. Without a doubt, Bush has spent the last half of his second term unravelling the fabric of much of his foreign policy because his previous methods were failing at every turn.

Yet, change he has.

After all, the Bush administration is well into negotiations — on one level or another — with numerous declared “enemies” of the United States, with particular emphasis on the “axis of evil”.

Obama’s policy of pro-engagement might feel visionary and new, but only because Bush has been so quiet in his engagement with these parties, unlikely to celebrate a policy that was dead last on his initial list of priorities.

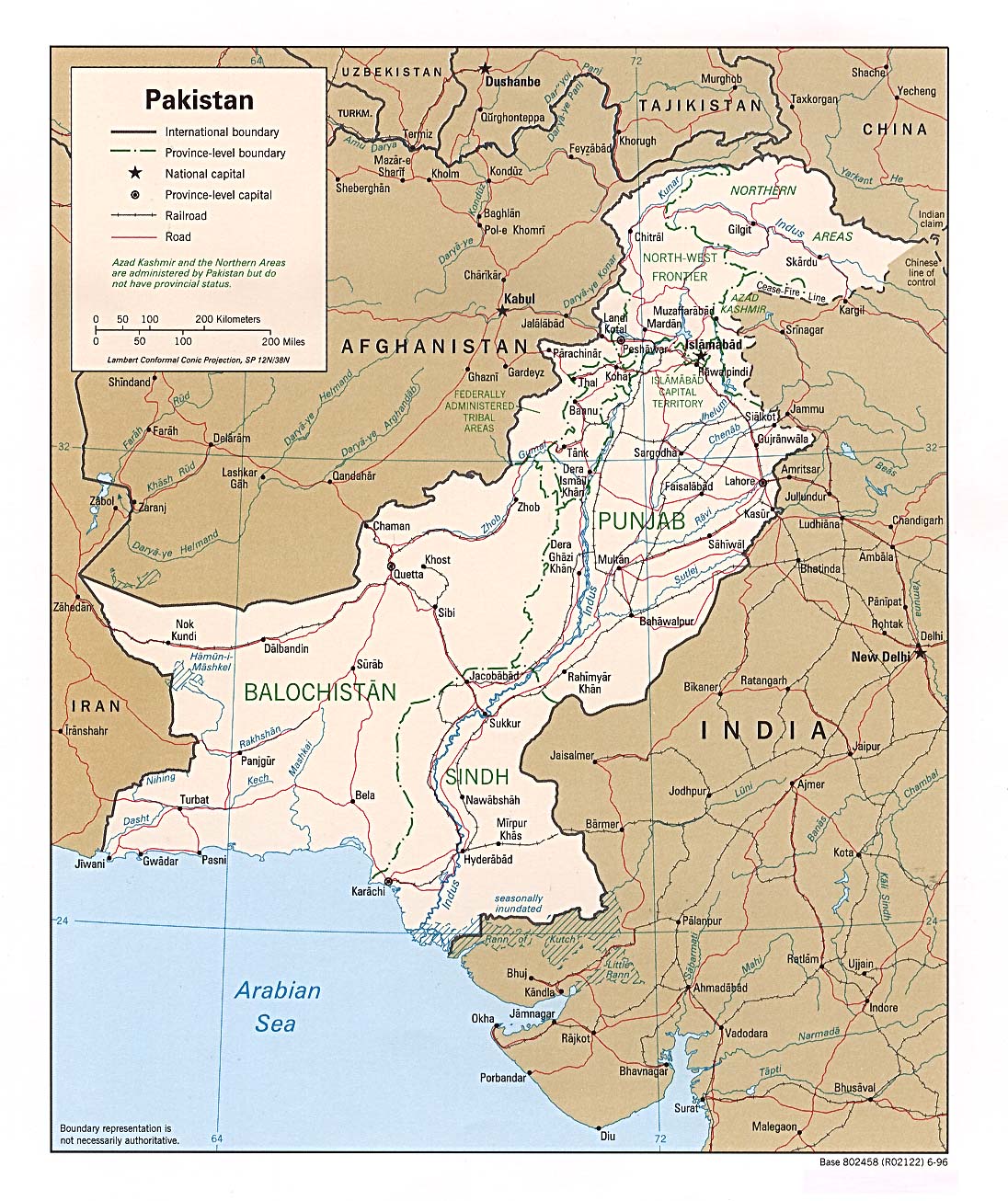

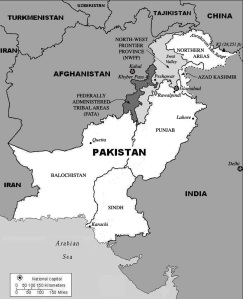

In order to provide a clean roadmap for his own foreign policy, Obama essentially ignored the seemingly pro-engagement tactics in the final two years of the Bush presidency on the campaign trail. However, it is no coincidence that Obama decided to keep Secretary of Defense Robert Gates at the Pentagon. For much of the last two years, Gates and Obama seemed to be virtually quoting each other’s policy speeches, especially regarding the importance of renewing US focus on Afghanistan/Pakistan in the so-called “war on terror”.

While most of us were distracted with how the presidential candidates framed their campaign objectives, Bush was busy creating the momentum for a series of negotiations that he never had the talent or political capital to finish.

If Obama, in contrast, possesses the talent and the capital to engage our adversaries effectively and with follow-through, then his best chance resides in his ability to complement, not replace, his predecessor’s recent diplomatic efforts abroad.

Reaching an appropriate balance of introducing new policy approaches and building on those of the past administration is what Obama’s transition team is supposed to ensure, but Obama’s supporters are expecting the appearance of clean breaks and fresh policies come 20 January, if only because Bush’s belated progress was inspired and stained by a failed presidency.

Obama has the benefit (and foresight) of knowing on Day 1 what his predecessor learned in Year 6, which might mean fewer political and military mistakes, especially the hubristic kind. If they do not succeed, however, he too will have to know when to change course.

There is frequently a healthy dose of wisdom that accumulates after years of defeat, and learning lessons the hard way doesn’t mean the lessons are any less valuable; it simply means they came at an exorbitant cost. Obama stands to reap the benefits of Bush’s about-face. To fully benefit from this lesson, however, Obama must acknowledge that while he was campaigning for change, change was already under way.

[View this commentary at the Common Ground News Service]

Below are my remarks (click to play audio) on the future of local defense forces and militias in Afghanistan at the American Security Project on 9 OCT 2012. I essentially argue that in two years, with few choices available, Kabul will deliberately instigate civil war in remote areas of the east and south to prevent open conflict in key population centers.

Below are my remarks (click to play audio) on the future of local defense forces and militias in Afghanistan at the American Security Project on 9 OCT 2012. I essentially argue that in two years, with few choices available, Kabul will deliberately instigate civil war in remote areas of the east and south to prevent open conflict in key population centers.

During an email exchange with my colleague

During an email exchange with my colleague